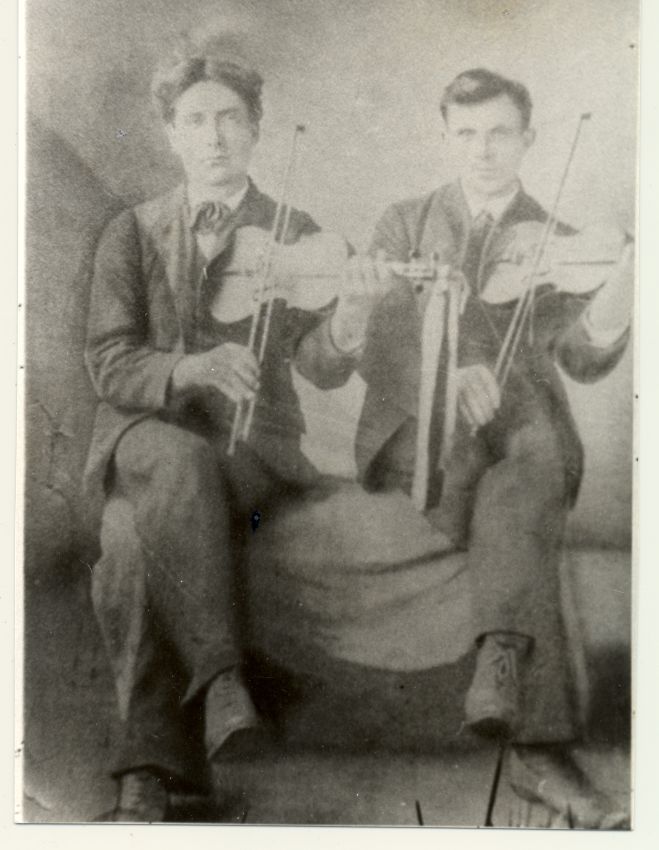

19th-century Traditional music culture

A Music Culture Rich In History

James Barry’s music manuscripts and diary provide insight into traditional instrumental music in Nova Scotia in the latter half of the nineteenth century. His documentation is particularly important because only a handful of early music manuscripts from Nova Scotia containing traditional-style tunes survive. Barry’s manuscripts provide rare clues as to the role of written/printed music in the dissemination of this repertoire, although there is little evidence available to show how common musical literacy was among Nova-Scotian fiddlers in the nineteenth century.

James Barry’s music manuscripts and diary provide insight into traditional instrumental music in Nova Scotia in the latter half of the nineteenth century. His documentation is particularly important because only a handful of early music manuscripts from Nova Scotia containing traditional-style tunes survive. Barry’s manuscripts provide rare clues as to the role of written/printed music in the dissemination of this repertoire, although there is little evidence available to show how common musical literacy was among Nova-Scotian fiddlers in the nineteenth century.

Even in Cape Breton, Nova Scotia, where much information has been passed down about the Scottish-based fiddle tradition, the picture is not clear. People believe there were always some music books in use there, but during the World Wars, fiddlers and pipers brought home many more old music books from Scotland, and musical literacy grew. For that reason, it can be difficult to determine when an old music book actually arrived in Nova Scotia. Written music in public performance has not been part of traditional music in Nova Scotia; books and manuscripts would be used mainly for learning new tunes and maintaining a larger repertoire than otherwise possible.

Barry compiled two handwritten music manuscripts. The larger of the two is over 650 pages long, containing 2247 tunes. His smaller manuscript consists of nineteen of his own compositions in traditional style, extracted from his large book where they are scattered among other tunes. Most of Barry’s large manuscript seem to have been copied from published books. Comparison with published music collections reveals many sequencies of tunes copied in the same order as they appear in print. Perhaps Barry borrowed music books (which would not have been common possessions in rural Pictou at the time) and diligently copied tunes into his own manuscript before he had to give them back.

Close to half of the tunes are Scottish, mostly strathspeys and reels. This fits with Barry’s Scottish heritage, which was shared by most of the people in his community. It also reflects the large number of Scottish tune collections that were published in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries (originally sold primarily to upper class patrons). In contrast, publication of Irish tunes mainly came later, so it is not surprising that only about five percent of Barry’s tunes are Irish. His large book also contains many hornpipes, some of which are Scottish or Irish, but most of which are from English or American sources. There are numerous polkas, waltzes, cotillions and quadrilles as well, which were played for popular dances of the time. Marches, song melodies, and some light classical pieces round out the variety of Barry’s large manuscript.

Where did the tunes come from? Barry obtained some from friends, transcribing quite a few himself. He often wrote annotations next to tunes, specifying who had provided them for him. These tunes were either already in aural circulation, or new tunes picked by his friends to learn. A few were locally composed. Barry sometimes noted his opinion about which of multiple versions of a tune he had found in books was best, and sometimes he made his own alterations, proudly writing “improved by James Barry.” He occasionally included instructions on how tunes should be played, and he also added cross-references as to which tunes went well together. Most of the tunes in his manuscript were probably not in his working repertoire, but he clearly enjoyed going over them and thinking about them.

His diary also provides clues. He often described his musical activities, such as the “balls” in attended. Most of the balls seem to have taken place in private homes, but “balls” may have been fundraisers, since Barry gave a price per couple (3/6) for one of them to which he was invited in 1860. In some instances Barry specified that there was a dance or a spree after a frolic; frolics were work parties in which neighbours helped each other complete major tasks such as ploughing or building a barn. Presumably there was often music after the work — or even during it — but Barry didn’t usually elaborate. In January of 1851 Barry wrote, “I had a frolic to-day drawing firewood for the kiln. Succeeded middling only there was a great gathering at night. Daniel [his brother] was in playing the pipes for them. I had to go to bed before they finished.” In November of 1860 Barry fiddled for David Ritchie’s ploughing frolic. In February of 1866 Barry complained about persons who were not working at his frolic showing up for the celebration at night. Towards the end of his life, there were fewer events like frolics, and he relied more on other ways of sharing his music.

Barry was an active participant in his community’s musical traditions, but he also sought to expand his horizons. Barry expressed admiration for fellow fiddler “Red” Colin McKenzie of nearby Rogers Hill, however he wrote that “Colin was a good old Niel Gow player of Strathspeys and Reels but …nothing…more — he played by ear wholly.” In his diary he remarked, “he knows nothing of waltzes, polkas, Quadrilles, Cotillions & Cet.” McKenzie was born ca.1793 in Ross-shire, Scotland and he emigrated to Nova Scotia in 1808. Barry transcribed at least twenty-five tunes from McKenzie’s playing and included them in his large manuscript. These represent an early aural tradition in Pictou that links directly back to Scotland.

Yet Barry seems to have been more impressed by the abilities of violinist/fiddler Finlay McIntyre, who showed up at his mill one day, and went on to be a major influence on his music. McIntyre was born in 1807 in Perthshire, Scotland and immigrated to Canada around 1830, settling first in Halifax. In Halifax, McIntyre taught violin and dance in a studio called McIntyre Hall. By the time Barry met him, McIntyre had moved to Truro and become a farmer. McIntyre had the kind of formalized knowledge that Barry thirsted for. McIntyre probably helped him develop his skills reading and writing music. After their first visit, Barry marveled that “he wrote 4 or 5 tunes for me just as easy as I could write the ABC.” Barry was inspired to start his own manuscript a year and a half after their meeting. McIntyre wrote some tunes into the manuscript himself early on, and Barry labeled later tunes as coming from McIntyre as well. In his diary, Barry wrote that McIntyre instructed him on hornpipe playing and “flats and sharps.” McIntyre may have been able to teach him more about advanced techniques such as position work, in which Barry was interested.