Rural Life in 19th Century Pictou County

A Miller, a Fiddler – A Life From a Quieter Time?

Maybe.

We tend of think of agricultural societies as slow places, but much of late 19th-century Pictou County was dynamic and modern. James Barry lived alongside communities where major industries such as coal, iron and manufacturing (and later glass, steel and railcar plants) dominated the landscape, and where great sailing vessels and steam ships regularly plied the waters between New Glasgow, Pictou, Montreal, Boston, and Liverpool. After 1867 a railroad connected New Glasgow and Stellarton to Halifax and Montreal. Barry availed himself of these advanced means of communication while vacationing in Prince Edward Island, purchasing supplies and visiting other musicians in Halifax, and reading books published in Glasgow and Philadelphia. There was a decidedly cosmopolitan dimension to some parts of Pictou County, and very much so in Barry’s life.

We tend of think of agricultural societies as slow places, but much of late 19th-century Pictou County was dynamic and modern. James Barry lived alongside communities where major industries such as coal, iron and manufacturing (and later glass, steel and railcar plants) dominated the landscape, and where great sailing vessels and steam ships regularly plied the waters between New Glasgow, Pictou, Montreal, Boston, and Liverpool. After 1867 a railroad connected New Glasgow and Stellarton to Halifax and Montreal. Barry availed himself of these advanced means of communication while vacationing in Prince Edward Island, purchasing supplies and visiting other musicians in Halifax, and reading books published in Glasgow and Philadelphia. There was a decidedly cosmopolitan dimension to some parts of Pictou County, and very much so in Barry’s life.

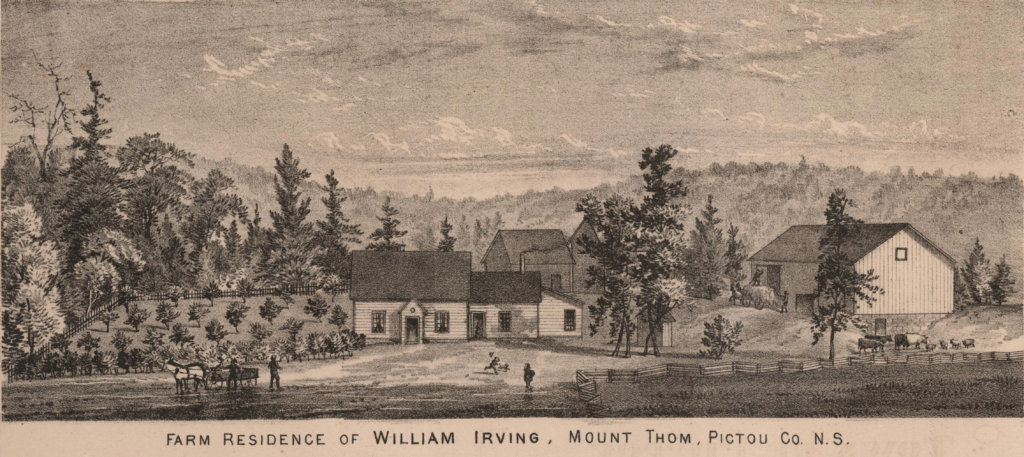

Still, the daily rhythms of life on Six Mile Brook were older and quieter than in the industrial districts. For the settlements along the West River, much more so than along the East River, life was primarily agricultural. In the 1871 census, the vast majority of men described themselves as farmers, with a smattering of millers, shopkeepers, skilled artisans and the odd professional in the mix. Across the county over a quarter of the population were now skilled tradesmen, but in Six Mile Brook it remained overwhelmingly farmers. And while there was a railroad station nearby at West River Station, most roads were poor; by far the best transportation was in winter when snow allowed sleighs for hauling grain and wood to the mill. The modern world was nearby, but in many ways still far away.

As the miller, Barry stood at the centre of his community. Those farmers and artisans were his main customers; they were also his neighbours with whom he most often socialised. Mills were critical infrastructure in agricultural settlements. Most everyone had grain to be ground – mostly oats, but large amounts of wheat, buckwheat and barley – and some purchased their meal and flour from the miller. And even poorly developed farms had timber to be milled. Perhaps like some millers he was regarded suspiciously. Most millers obtained their pay in a “toll” – that is, a portion of the grain ground – and many customers no doubt believed he took more than his share. The mills were also social centres: where neighbours met and exchanged news and views. Barry’s diary makes clear that he learned much about politics, events in the surrounding countryside, marriages, deaths, weddings, frolics, the state of crops, and the prices to be obtained. In the spring, Barry turned his attention to lumber and shingles, as lumbermen-farmers “hawled” their timber out of the woods. The mill was a social and communications hub.

As the miller, Barry stood at the centre of his community. Those farmers and artisans were his main customers; they were also his neighbours with whom he most often socialised. Mills were critical infrastructure in agricultural settlements. Most everyone had grain to be ground – mostly oats, but large amounts of wheat, buckwheat and barley – and some purchased their meal and flour from the miller. And even poorly developed farms had timber to be milled. Perhaps like some millers he was regarded suspiciously. Most millers obtained their pay in a “toll” – that is, a portion of the grain ground – and many customers no doubt believed he took more than his share. The mills were also social centres: where neighbours met and exchanged news and views. Barry’s diary makes clear that he learned much about politics, events in the surrounding countryside, marriages, deaths, weddings, frolics, the state of crops, and the prices to be obtained. In the spring, Barry turned his attention to lumber and shingles, as lumbermen-farmers “hawled” their timber out of the woods. The mill was a social and communications hub.

This social dimension of mill work overlapped with his music. Barry was a known figure in the community, and surviving lore suggests he was not well regarded by some. But the many people passing through, the many conversations taking place, no doubt connected Barry with music and other musicians. Much of the music in Barry’s larger collection was directly copied from other music books; these are well-known tunes and in many cases we see standard versions reproduced here in his manuscript. But Barry notes in the margins indicate that many he heard from another fiddler. Barry position as the owner of the mill greatly enhanced his position as a collector of tunes and a curator of local music knowledge.

But we can also see how modern transportation and communication shaped Barry’s relationship with “traditional” music. Many of the tunes Barry transcribed he heard when someone passed by the mill, whether to meet Barry the musician or Barry the fiddler. But equally often Barry heard music on the steam-ship to Charlottetown, or a music hall in New Glasgow, or taking the train to visit other well-regarded fiddlers in Halifax and Truro. Perhaps most importantly, modern cheap printing also gave Barry access to hundreds of tunes, notably ones published in Scotland and the United States – but which appeared in Pictou bookstores within weeks of publication. James Barry’s encounter with a “traditional” world was very much shaped by living in the modern world.Barry stood at the